When we moved to Maine in 1989 and my bi-racial son entered 3rd grade, I did not foresee that there would be problems in school, but it wasn’t long before I knew something was wrong. One morning, he hid under the bed covers, crying and saying he hated himself. Finally, he admitted that the kids in school were calling him “Chocolate Boy” and refused to play with him. They told him he belonged in the back of the bus, and when they lined up at the end of recess, they shoved him to the back of the line.

I demanded that the school do something about the mistreatment of my son, so the guidance counselor went to the classroom and talked with the students about the “problem”. I knew it would hardly be enough of an intervention, and much of the ignorance extended beyond the classroom. Some of the white families had never actually seen a black person in person, let alone in the books they read in school. It was like trying to put out a sea of flames with an eye dropper.

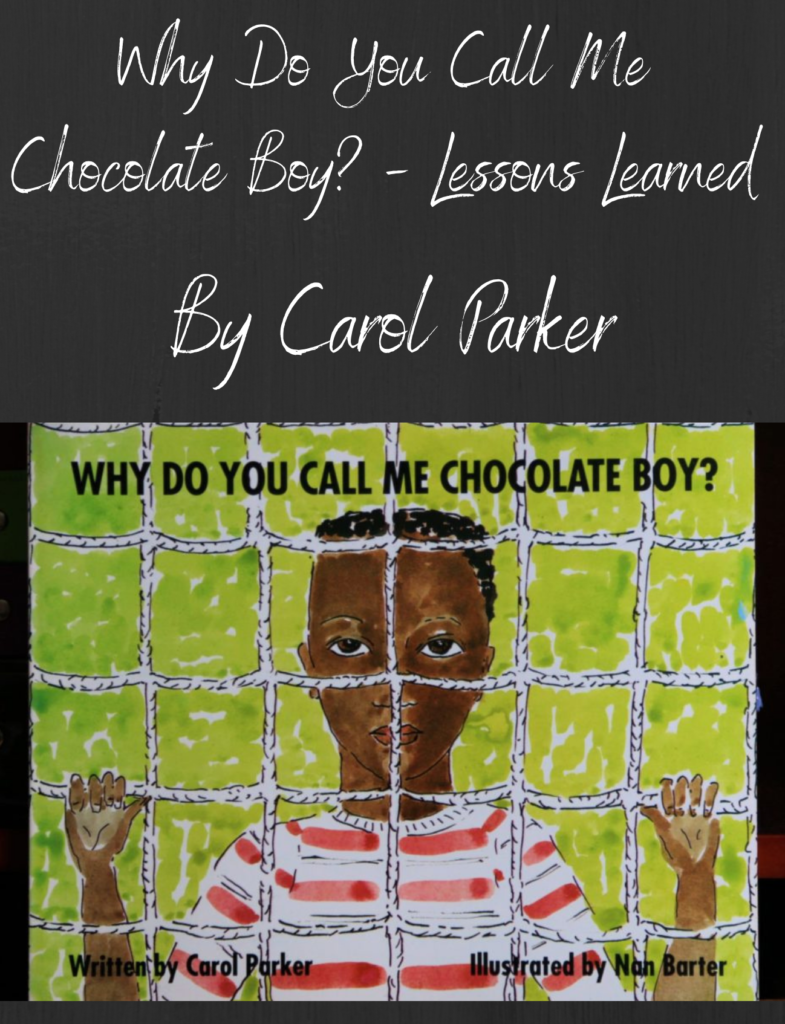

I decided to take matters into my own hands by writing WHY DO YOU CALL ME CHOCOLATE BOY? It was the best way I knew to protect my child and to dismantle racist mindsets. My sister Nan Barter, a talented artist, created the illustrations for the picture book, and in 1993 I self-published it.

In retrospect there are many things I would have done differently if I could do it again. The urgency to fight racism led me to move too quickly to get materials into the classrooms and into students’ homes—tools to teach them about the roots of racism in our culture and ways to build respect for one another through honoring diversity. I should have taken more time to ask for feedback from others, especially from people of color, and I should have had my manuscript professionally edited before sending my final draft to the printer.

The cost of publishing was another factor. Color illustrations would have been nice, but my budget only allowed me to colorize the front cover and two illustrations inside.

When it came to distribution, I knew little about marketing, and in the early 90’s, the internet and social media were infants. Nor did I have the confidence to network and promote WHY DO YOU CALL ME CHOCOLATE BOY? the way I should have.

Despite the book’s relatively short life, it rippled through the hearts and minds of many locals. When I picked up the books from the printer, he asked for a copy to read with his children. It meant a lot to me when a mother would stop to tell me that WHY DO YOU CALL ME CHOCOLATE BOY? was her daughter’s favorite book, and they read it together every night. And teachers used it in their classrooms. At first my son was embarrassed, but years later he shared copies with his friends and told them how proud he was of his mother. That alone made it worth writing the book almost three decades ago, but it’s a shame this country is still dealing with racism in 2021.

Wow! Good for you, Carol. We do the best we can with the resources and knowledge we have at the time, and it seems like you did make an impact. You were anti-racist before it became a buzz word.

Thank you for sharing the backstory Carol. I imagine that was a difficult time. But I think it’s wonderful you did something to help change hearts and minds.